For a long time, even after the Doc Hare rein, the Group was a leader in the television industry, and the movers and shakers of the industry would trek to Grass Valley to witness what the company had to offer, and to seek solutions for technical issues they faced. At some point that spirit of being out front and leading the way gave way to a more cautious and buttoned down way of doing business. Many would argue that that was Tek's doing, and in many ways it was. But some of it might be that the company out grew the small town mindset that the towns of Grass Valley and Nevada City had. It's roots were definitely in the area, and at one time the setting in the foothills of the Sierra was a recruiting tool in itself. But times and attitudes inevitably change, and towards the end of the book we'll look why that is.

We will now look at the leadership that ushered the group from a proud prize of Tektronix, to being cast off after 26 years in Tek's camp.

Dan Wright

In April of 1983 Tom Long left Tektronix to go east to work for Analogic, in Peabody, Massachusetts, where he was the Executive VP in charge of Operational Management. Long, was the President of the Group for nine years. At the time GVG's Management Council said, "Tom's expertise and leadership during his 23 years at Tek have been a great asset to our company. We will miss him and wish him well in his new venture."

Long was not a good fit in his new position and locale, he was back the next year as the VP and GM of Tektronix's Design Automation Group, and the President of the Tektronix Development Company, where he ran Tektronix Labs, in Beaverton.

While he was only gone from the company for a year, it left an opening for Dave Friedley to move up. Tektronix EVP Bill Walker said, "Dave's experience with both the Communications Division and the Grass Valley Group make him well suited for his new responsibilities. The Communications Division and the Grass Valley Group have, over the years, maintained their leadership positions in their respective markets. Dave's expertise and leadership will greatly contribute to the Division's continuing record of success." Friedley, his wife Carol, and their three children relocated to Oregon.

Now for the first, and only time a leader from the Group started their rise up the top of the parents corporate ladder, instead of being "sent down" to oversee the Group. This demonstrated that at the time Tek was happy with Grass Valley's contribution to the larger organization. Is this statement correct?

![]()

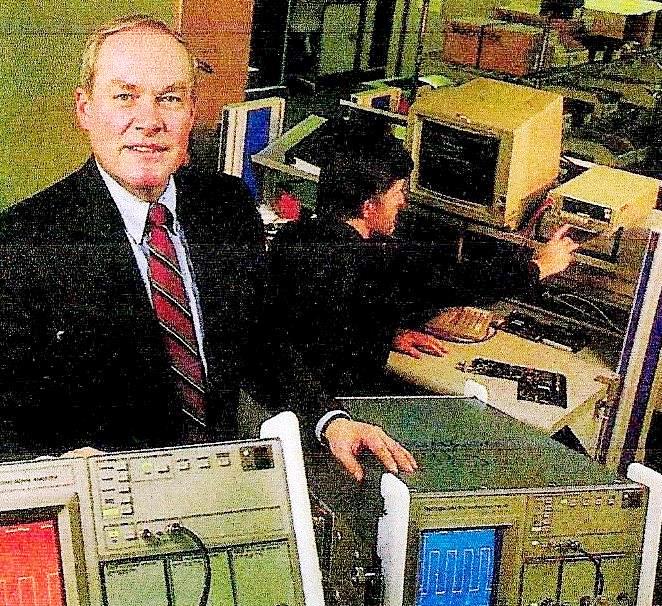

Before Dave left for Tektronix he made Dan Wright Executive VP. Wright promoted David Mayfield to Modular Product Division's GM as his replacement. (A bit fuzzy on the trajectory of Mayfield: Was he MPD marketing, then its GM, later moved to PVD GM, then Group GM?) Wright had been a manufacturing engineer, who was instrumental in getting the 300 into production. Under Wright the commitment to "divisionalization" continued. Some thought that this devotion to the concept created silos and internal competition that was destructive to the morale of the employees. It was also claimed that he tried a number of McKinsey and Tom Peters type strategies. One such strategy was management by walking around (MBWA). That one seemed to work as Wright was known for actually visiting, and even performing tasks that "on the ground" employees did.

![]()

Dan Wright trying his hand at component assembly

Most thought Wright was a nice guy, but even practicing MBWA he never quite understood how people worked. He was not a pure technologist, so at times he did not understand the technical ramifications put before him.

Dan was a manufacturing engineer in Tek's spectrum analyzer group when, in 1979, Dave Friedley brought him to GVG. GVG was having difficulty (what difficulties?) moving the 300 production switcher from engineering to manufacturing, and Friedley hoped that Dan would be able to help. Where the Group needed help was for the first time, with the 300 production switcher, the company was striving to produce a high end product that even with a boatload of options, could be treated more as a "massed produced" product instead of a continuous series of "one-of" job-shop products. Wright had that experience through Tek, while no one in the Group did at the time. He was successful in doing so, so when Friedley decided to "divisionalize" GVG, he chose Dan as the general manager of GVG's first division, Modular Products. Wright continued Friedley's efforts to "Tekify" GVG.

In fairness to the whole "divisionalize" concept, it could be argued that the fact that the Bitney Springs site couldn't be grown much more, and as we saw that nature and local government was making the site untenable. That left a couple of choices. To expand off site, and to start they could have just moved the Modular Products manufacturing into leased space and have it continue reporting through Jerry Sakai up through the Bitney Springs hierarchy. But with the decision to buy the Providence Mine site, the future was going to be a more geographically dispersed company. At the time no one had an inkling that eventually that dispersal would be world wide as we will see.

Dan Wright grew up in Monticello, Indiana and graduated from Purdue University in 1968 with a degree in engineering technology. He went to work for Collins Radio in Cedar Rapids, Iowa before joining the Air Force during the Vietnam war. Five years later he left as a captain with extensive experience conducting evaluation missions for the Aerospace Defense Command.

He joined Tektronix in I974 as a design engineer. Five years later he was a manufacturing manager when he signed on at GVG. In 1980 he became the manager of MPG.

It was said that Fridley was Dan Wright's rabbi. That is without any religious or spiritual significance, "a primary sponsor or protector", also means a "mentor or teacher". Both were true in Friedley's case.

Extremely successful 100

small production switcher

In 1984 the 1680 production switcher, the panel laid out to be familiar to 1600 users, but with many 300 features, and the enormously successful 100 small production switcher were introduced. That year Wright oversaw the Groups acquisition of Dubner Computer Systems. This allowed Dan to check the box "did an acquisition." The fact that the folks at ABC, still the Groups biggest customer, liked Dubner products made it an easy sell to Tektronix and the Group's customer base. Julius Barnathan ABC's head of engineering was instrumental in putting the deal together because they had a pretty significant investment in Dubner equipment and weren't confident that Harvey Dubner, founder and CEO, could really run a company successfully. In the end, the Dubner acquisition was not very successful because Wright and those that followed had no clue how to manage Harvey. The brand was retired by the Group in 1991.

In 1984, the 25th anniversary of the Group, somebody concocted a story (what was the story?) to lure Doc Hare to come to NAB and Bill Rorden flew him there in his plane. The event was honoring Doc and ABC was the presenter. In the first shot the players left to right are Dave Friedley, Helen McMillen, Bob Cobler, Julius Barnathan (VP engineering at ABC), Jerry Sakai, Doc Hare, Birney Dayton, Hazel Hare, Vern Pointer (Executive VP ABC), Max Berry (One of ABC’s top engineers), Dan Wright, Bill Rorden, and Bob Johnson.

1985 brought a few new milestones. A new audio/video router, the Horizon, and a new line of modular products, the 8500 was introduced.

Wright also did another acquisition, Interactive Systems Company (ISC). Dave Bargen started his company after several large post companies on the U.S West coast wanted to upgrade or modify their existing online CMX suites but weren't prepared to wait for Bill Orr's company to release an updated CMX editor. CMX was a joint venture started by CBS (the C) and Memorex (the MX) to build what became the first sophisticated video tape editing system. These systems were not small (as we have seen), nor were they cheap, complete systems would cost between $60,000 to $200,000. They consisted of a DEC PDP-11 mini-computer, and what were called Intelligent Interfaces (or I-Squares), one was needed for each device that was to be controlled. In the 80s memory was expensive, microprocessors were a number of generations from being capable enough, so instead of desktop editing as done today, you needed a room full of equipment. So those post houses commissioned Bargen to create new software that added extra features to the existing CMX hardware.

The software came to be known as 409, as it claimed it cleaned up the "bugs" in CMX's software.

Bargen knew that for ISC to be a long term success he would need to include the ability to control video and audio peripherals. His own version of the I-Square. Bargen's longtime friend, Vidtronics chief engineer Jack Callaway was an expert on VTR machine control. Callaway and Bill Gordon reverse-engineered the CMX interface protocol, and built a simpler, and smaller interface. Where the CMX I-Square was about 12 inches high, Callaway's was less than two inches tall.

The units became known as Callaway boxes and allowed ISC to offer editors an alternative. Complete ISC systems sold for $30,000 to $50,000. This system spelled the start of the end for CMX. While CMX could of built a smaller I-Square at the time, internally the justification for a larger box was how could they charge over $10K per I-Square it the unit was much smaller.

The other nail in the coffin was the introduction of the RS-422 remote control standard. As we saw earlier RS-422 was a godsend to NVISION, in a search to find relevance, started making RS-422 routers. But it undermined the business model that CMX had thrived on up until that time. Up until then each I-Squared required different hardware configurations based on the particular device being controlled. Thus an I-Squared configured for one device could not be used with a different device. Although first introduced in 1975, RS-422 started being incorporated into devices in mass by the mid-80s. RS-422 made it easier to connect I-Squares to different devices, usually allowing a facility to require fewer of them. Once CMX, and others went to RS-422 control, the hardware was always the same, all that changed was the firmware. The Group was now squarely, in the editing market.

That year also saw the infamous meeting with Sony at NAB over the Group productizing and offering an analog HDTV version of the 300. Wright wanted to see a market first. Up until that time the Group usually responded to customer requests, very often from ABC, before proceeding with a product. Sony was the opposite, as they were in more of the television food chain, both consumer and broadcast, than the Group was. Color TV set sales were flattening as color set penetration was nearing saturation, and Sony was looking for a reason for people to buy more sets. Just as RCA had commanded NBC to produce all shows in color at the start of the 60s to sell color TV sets, Sony was trying to create a new TV market it could sell into. They were taking the long view. The Group could not or would not do the same. Some of the blinders for not seeing a coming new technology, that is higher video quality, in the form of HD, could be laid at the feet of ABC. ABC as mentioned viewed Grass Valley as their equipment development arm. There was always a need validation if ABC wanted something new. ABC had no interest in HD at that time. Plus the Group's limited resources were tied up with the their first Digital Video Effects engine, the Kaleidoscope; and it was an abitious project as we have already seen.

At the end of 1987 construction at the Providence Mine site finally commenced on the first three buildings. When it was originally bought at the end of 1982, the intention was to use it for additional growth, which many thought would keep happening in the area. The thinking at the time was that the company's growth rate would continue at 15%. The Bitney Springs site was rapidly being built out to capacity, and the environmental cost were rising at that site. The new site was planned to hold 2000 employees in a dozen buildings. Being only 500 feet from a main water line, and adjacent to Nevada City's wastewater plant with easy freeway access, and secluded at the same time, it seemed like a good move. As we have seen there was another reason for the new campus. Bitney Springs was becoming untenable.

In 1987 Friedley made it to the top of Tektronix. He replaced long time president Earl Wantland. The company wanted a person that would freshly address the issues that were building at the company. While Friedley had started at Tek, and was sent down to the Group as its first Tek minted manager, the company in the 80s had done well. The company was "on top of its game." He replaced Tom Long in 82 when he left as the head of the Television Division at Tek. From his Tek vantage point, as head of the TV division he and Wright sheparded the Grass Valley operation with steady growth. The Production Systems Division (high end switchers and DVEs) and the Professional Video Division, (low end switchers and DVEs), both saw a dramatic growth spike during that time. But all of the company's divisions saw decent growth during the period. Those were the heady days of the Group. When it was time to replace Wantland, the division manager who oversaw Grass Valley, one-half of the revenues of the Television Division, seemed like the natural choice.

At the same time Friedley replaced Wantland, he could not have ascended to head Tektronix at a worst time. Tektronix had acquired CAE Systems Inc and introduced its first Computer Aided Design (CAD) workstation. It was short-lived. Four months later, the company announced that instead of producing Workstations, it would develop software for other manufacturers. That too faltered. So one of the first things Friedley did was to sell its CAE operations at a fire sale for $5 million to Mentor Graphics. Estimates of Tek's losses from this ranged from $150 million to $225 million.

When Friedley became Tek's CEO he replaced three of the four top Tek Vice Presidents. Wright ran the Group up to 1988 when Friedley used Wright as his replacement again, and Wright assumed the VP title for Tek's Communications Division, which was newly formed at the time out of the TV Products Group. It was comprised of the Group, Tek's Video Products, Network Analyzers, and Tek's Hybrid Circuits. Wright tried to do this job from Grass Valley and not move back to Oregon.

Besides Wright, Friedley made Larry Kaplan, who was the head of the TV Products Group, the VP of the newly formed Information Display Group. This group had workstations, terminals, printers, and the printed circuit board operations He will become more predominate shortly.

Despite annual revenues that had almost doubled in ten years to $1.4 billion in 1985, they had stayed there since. Tektronix reported its first-ever loss of $16.7 million for fiscal 1988. Friedley later told Forbes, "The first thing we did was stop the bleeding." In addition to getting out of unprofitable businesses, Friedley eliminated 2,500 jobs at Tektronix over the next two years. Business Week reported that Friedley "cut through bureaucracy like a logger through the nearby Oregon timber." But it was not enough. Tektronix returned to modest profitability in 1989, due to stringent cost-cutting and a new line of color printers. But its financial troubles were far from over.

1988 was a bad year for the Group also. As we saw in chapter 9, on September 11th the 49er fire started. It burned through part of the Bitney Springs site. Luckily it only took a couple of ancillary buildings. But Tek suddenly realized that they had a company that was doing $129 million of income a year in a place that could literally burn up during the long dry season that occurs in California every summer, and into the fall.

A bright spot was the Kadenza, the result of turning the Kscope DVE into a full standalone switcher, which started shipping.

During the 80s the Group, from a growth standpoint had a very good run. At the start of the 80s the Group was below $50 million a year in revenue, by 89 it had grown steadily to $158 million. At the start of the 90s that growth hit a wall.

Dave Mayfield

Dan Wright appointed Dave Mayfield as his successor as Executive Vice President and GM of the Group. Mayfield had been the division manager of another division formed a couple of years prior, the Professional Video Division (PVD) which was the small switcher division at the time. Many were surprised at this appointment, because Mayfield had no experience at all as a manager of multi-functional groups. Some said his only apparent "qualification" for the top job at GVG was that he was a close personal friend of Dan Wright's and a member of the same evangelical church as Wright. (Again a bit fuzzy on the trajectory of Mayfield: MPD marketing, than PVD GM, then Group GM?)

Randy Hood, who was the division's marketing manager, took over MPG. Correct?

During Mayfield's time the company launched a new switcher line, the Diamond, which was an analog switcher, and a new DVE, the DPM-100.

The company was still considered novel and eccentric, but in interesting ways. Located about 150 miles northeast of San Francisco, Grass Valley Group had its own airplane to fly customers in and out of the remote, wooded company headquarters. Some of the Group's lure as an remote outpost was at that time considered "a plus and minus when it came to recruitment," according Mayfield.

An article by the LA Times at the time mentioned the following: "Designed to appeal to "free-thinking" employees (one company executive ventured to call them "mavericks"), flex-time schedules are available for most of the nearly 1,000 workers who work in Grass Valley. Assemblers work in self-managed "cells" rather than production lines, rotating jobs and setting their own production goals. As an added incentive, a profit-sharing program was introduced in 1976."

The article continued: "A fitness trail winds its way through the 330-acres of campus-like grounds and fleets of bright turquoise company bicycles are parked outside each of nine buildings to carry employees and visitors about the grounds. And if the habits of the free-thinkers at Grass Valley Group sometimes border on the eccentric, so much the better. One department is so adamantly unorthodox that if an outside salesman makes a call wearing a necktie, he'll more than likely lose it--to a pair of scissors, according to Bob Johnson."

Friedley Out

David Friedley

The start of the 20th century's last decade was going to be a tumultuous time for both the Group and its mother ship. In early 1990, the company was again posting losses, Tektronix stock had fallen in value from $31 a share in 1987 to a 14-year low of $12.75 a share. In 1990 Tek posted a loss of $25 million, and sales were down 3%. Tek's main competitor in the test equipment realm was HP. In 1980 Tek was 1/2 the size of HP, by 1990 Tek is only 1/8th the size. A financial analyst for Prudential-Bache Securities, Inc., told Business Week that meetings with Tektronix "were like watching the grass grow." The anticipated shake-up came in March of 1990, with the company headed toward a $92.5 million loss (largely due to restructuring) for the fiscal year. Robert Lundeen, a former Dow Chemical Co. executive and Tektronix's chairman of the board, and William Walker, another board member, ousted Friedley and took over operational control of the company. Even though 62% of Tek's products had been introduced since 1986, they told Friedley that the turn-around just wasn't happening fast enough.

Many signs that the company was moving in the right direction were seen in the printing division, which had grown rapidly to $90 million in sales. New graphic terminals which had previously take three years from conception to production were taking only nine months instead of three years. A speedup in the design process was one of Friedley's goals. Another thing that was facing Tek, was systemic to the economy, a business slowdown was happening and Tek's largest customers, Defense, computers, and semiconductor companies were looking to cut costs.

Not all was positive. Tek's latest workstations were having software problems, and problems with Tek's semiconductor fab lines were delaying the shipment of test equipment. On the workstation front the company only had 3% of the market and its prospects for securing much more were bleak. Friedley also found that many in the company's engineering staff didn't focus near enough on the end customers needs. He was quoted as saying "I'm sure some of our whiz-bang people wouldn't know a customer if they saw one." The problem was not that the company was not investing in the future, it spent $190 million on research and development in 1989. The problem was many felt that the company wasn't getting a decent 'bang for the buck' from the money spent.

Some, including their main competitor's CEO, HP's Dean O. Morton said that they lacked a clear strategic vision and he said "They've had a difficult time figuring out what they want to be." Ironically HP confronted a similar problem a decade later when they spun off all the legacy product lines into Agilent Technologies. and kept only printers and computers. In 1990 Tek had a similar product mix. Printers, which were ascendant, test equipment and semiconductors, experiencing mixed results, and the increasingly burdensome television product lines. The company's major investors had become inpatient. At that time a couple major investors started saying that they thought the company was worth more split up than whole.

Citing the need to reverse the financial losses, Lundeen told Portland's Business Journal, "I don't think management realized how urgent it was that we get there quickly." Lundeen told Forbes, "I'd like the new Tektronix style to be more cosmopolitan," and he complained, "We're still doing things the Beaverton way." Lundeen initiated another 1,300 layoffs. In a blow to it's corporate image, Tektronix also transferred more than 1,200 workers from Vancouver, Washington, to Oregon, leaving vacant a 488,000 square foot manufacturing facility in Jack Murdock Park, an industrial center named for the company's co-founder. For years, Tektronix had been the largest employer in Oregon, with a high of more than 24,000 employees in 1981. But by the end of 1991, the company had a work force was less than half that.

Wright Gone

Birney Dayton said that Mayfield's promotion was the last straw that caused him to leave and start NVISION. With Mayfield the company' status quo, which was already fraying, seemed intact. Before Dayton left, Tektronix had bought a company down in the bay area called LP communications that made a T1 tester. Birney and a few others, along with the LP heads convinced Wright to combine those operations, along with Wavelink into one standalone entrepreneurial operation to make it worthwhile to operation to develop and market. Wright became convinced finally to not only spin this group off but that all of Tektronix should be split off in this way.Wright pitched the Wavelink spinoff to Fridley, who didn't take kindly to Dan's proposal. The idea was that the parts were worth more than the whole. Friedley thought that would drive the company into max short term profit to get the max return on selling the company in parts.

Wright had pondered at times if it would be better if Grass Valley and Tek divorced. It was reported that had others had started advocating for the leveraged buyback of Grass Valley from Tek. Rumors flew that Sony was approached about buying GV. Most of the Tek board was having none of it at the time, even though, as mentioned some were already pushing that exact line of thinking.

Also from chapter 9: was a Wavelink spioff ever pitched. did Wright ever propose any of this?

When Friedley was let go, the lieutenant he had promoted, Wright, was unceremoniously informed by phone, that he was out of the company also. Why? The company also for the first time, started looking for the next CEO outside of the company.

Larry Kaplan - Tek VP and GV GM

Larry Kaplan

Calamity was not only happening at the mothership; it was happening locally also. On Friday, November 16, 1990, Dave Mayfield, CFO Don McCauley, PSD GM Randy Hood, and PSD Engineer Dick Jackson, resigned from GVG "to pursue other interests outside of the Grass Valley Group." They tendered their resignations via letters FedEx'ed to Larry Kaplan, who had replaced Wright as VP of the Communications Division. As it would later become apparent, all but Mayfield left to start Immix, which produced a desktop editing system called VideoCube which would compete with the Group in that arena. Carlton Communications financed the new venture. Carlton also owned video equipment vendors Abekas and Quantel. Both competed against the Group in DVEs, and Quantel also competed in routers. Mayfield was not part of the Immix group, but joined Abekas as V.P. of Operations. Mayfield would eventually end up at BTS in Salt Lake City. We will see how BTS fits into the Group saga later. Randy Hood ended up as the head of the new company. To lose that talent, along with one of the Groups top digital designers, in short supply at the time, Dick Jackson, came as a blow to the Group, and Tek. In the wake of those resignations, Tek dispatched Larry Kaplan to Grass Valley to try to keep the troops under control.

Kaplan joined Tek in 1974 as a video sales engineer. He received a BSEE from the University of Wisconsin, and later a MBA from Rutgers. He went to work for ABC before joining Tek. In 79 he became a product marketing manager in the TV Business unit, and rose to the Marketing manager in the group. He then became the business development manager for the Communications Division in 1982. In 83, at the age of 32, he rose to head the Information Display Group.

Kaplan was put in charge of the Communications Division, and also assumed the presidency of Grass Valley. In a memo to "all employees" after Mayfield and company had left, Kaplan wrote, "As president of GVG, I have assumed day-to-day operational responsibilities. The key management team is intact and expects to function with your full support." In the weeks and months that followed, Kaplan held periodic managers meetings to address any issues that arose, and to provide updates on the search for a new person to lead the company.

One who worked with him at Tektronix said he had a realistic view of himself. Before this calmity he had been the operating head of the Information Display Group, which included the Workstation, Terminal & Printer divisions. He knew he was over his head when he was in charge of Tektronix workstations. When he was charged with GVG oversight, he knew that he faced a difficult task.

Larry Kaplan came down once a week to let people know the GV wasn't going away, and to report on progress for finding a new president. One thing he did in early 91 was to partially undo the Group's "divisionization." He merged the Professional Video Divisions into the Production Systems Division, which he and Bob Cobler ran until Kaplan found a new Grass Valley GM, and the Modular Products Division and Switching Products Division into a new group called the Distribution Systems Division, which was managed by Craig Soderquist. The company still had separate groups for the Wavelink product line, part of the Telecomm Systems Division, and the Dubner Computer Systems group.

Another thing he did was to sack Jerry Sakai as they weren't seeing eye-to-eye on the company's re-organization. Of the original management group that left only Cobler.

Eventually he found a guy he had worked with for a long time, Bob Wilson. At one time Ampex was Tektronix's largest customer for monitors and scopes, as every VTR shipped with one of each. Wilson had run Ampex's VTR group.

Video monitor and waveform monitor highlighted

Bob Wilson

Wilson came on board in 1991 as the President and CEO of The Grass Valley Group, Inc.. Almost immediately it was apparent that he was too buttoned down for the area. His background was financial, not engineering. Also, he never committed to being a part of the local community. His career started at Ampex, the inventor of video tape machines, and a general competitor to the Group in the television production equipment arena.

Ampex was located on the San Francisco peninsula. At Ampex he held various senior management positions, including Vice President and General Manager, Marketing, Sales and Service; Vice President and General Manager, Magnetic Tape Division; Vice President and Chief Financial Officer; and Assistant General Manager, Audio/Video Systems Division. He had a brief stint at another company as the Executive Vice President, Chief Financial Officer and Director of the Wickes Companies, Inc. before coming to the Group.

In early 1991, at one of his regular meetings with Group managers, Larry Kaplan announced that he was about to close a deal with former the Ampex executive, to become the new head of GVG. Larry spoke glowingly about Wilson, and indicated that he would be joining GVG shortly, before the 1991 NAB show. After Wilson was onboard, at a pre-NAB press event that Jay Kuca had put together in New York, Wilson was given a detailed briefing document that outlined what the company would be introducing at that years NAB. Wilson immediately went "off script," as he was prone to do, and announced that he was "going to put GVG in the video recording business." He made that announcement based on something he had heard about an ill-fated project to develop an uncompressed Digital Disk Recorder, code named "Merlin." At the time, engineering had not even produced a working prototype, and as Kuca recalls, they never managed to get the product working properly. That was the beginning of a long and stormy relationship he had with Wilson. At one point Wilson tried to get Kuca fired, but he had built some very strong alliances with a number of senior GVG people, and Wilson did not prevail.

Another notable time that Wilson went off script was at a Tek conference at Salishan lodge on the Oregon coast. Dan Castles, who was reporting to Kaplan at the time, was told by Meyer, the then Tek President (he'll be introduced shortly) that Kaplan's group had an hour for their part of the presentation. Kaplan, Castles, and one other went first, and Wilson last. Each had been allotted 15 minutes for their presentations. Wilson went 50. Kaplan got reamed for it. This did not help Kaplan's standing with Meyer. While Kaplan gave Wilson the proper feedback, Wilson could care less. He was known as a big talker.

Part of the problem was that Wilson never managed to build his own alliances within the company. Wilson sailed and spent weekends with friends in the Bay area. Everyone got it that Grass Valley was not home, and thus it never endeared him to the locals.

Wilson ran the show during dark days for the Group in the early 90s. One of those challenges was trying to consolidate the company at the Providence Mines site in Nevada City, and vacate Bitney Springs and the airport sites. The plan originally was to move the 40% of the area employees out of those two sites and to the Providence site. At the time there were three buildings at the Providence site, with a fourth one in the planning stage. With the financial situation facing the Group at the time that building was put on hold, and ended up never being built.

On the engineering and product front the Group had another problem. Other than the crew working on Kaleidosope, the Group didn't have many engineers who had a clue about high speed digital technology because the whole background of the company to that point was analog. There may even have been some outside influence in that GV had designed new product around the needs of ABC for a couple of decades and Julius Barnathan, ABC's Engineering VP, was firmly opposed to the digital TV transition, which may have left GV without their historical guidance.

About that time Wilson made a big bet on fiber, with a project called Excalibur, for Williams Communications. They wanted to put fiber in their oil lines. The project failed and the Group lost over a million dollars.

He also pushed for the Group to get into the virtual studio set market. Virtual studio sets are chroma key technology on steroids. In a virtual studio, say a news set, the only thing real is essentially the people on the set, and what they are sitting on. Everything else is usually a sea of green. The problem was that the technology was not quite there in the early 90s, and the Group didn't offer enough of the food chain, namely cameras, not yet anyway. It went nowhere.

In 1991 and 92 a recession hit, and the Groups sales dropped. At the time the Kscope DVE was being replaced by a newer version, called Krystal. Routers were headed up by the 7000, they had glue products, the editor was Sabre, what had evolved out of the ISC editor. The 3000 switcher was shipping, and the 4000 component digital switcher was getting ready to launch. The problem with all these new products is they couldn't defend and push them all out the door very well. The Group was shipping very shaky version 1.0 products. In one year GV went from a $20 million profit to losing money.

Amidst all this activity Wilson decided not to increase engineering pools but took on more new products none-the-less. It became hard to defend so wide a territory from competitors. At the time the Group had two ascending adversaries, Sony, and Ross Video. While not rising, Ampex was in the game also. There was also a number of players in Europe. Ironically, eventually all those European players eventually became part of the Grass Valley story.

We looked at Sony already. Ross was started by John Ross, a former engineer with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation in Iroquois, Ont., in 1974 to make production switchers. Jim Leitch, founder of Leitch Video, another fairly prominent video company that was eventually acquired by Harris, initially suggested that Ross start the company. In 1978 Ross launched its second generation switcher. By 1983 they had their own version of Emem, and two years later a third generation switcher. By the 90s they had branched out into a line of modular products. In fact Leitch video was also a capable player in modular products as well. The Group had lots of competition. Tektronix took notice.

In the summer of 92 the Soros Group stated buying up shares of Tek stock, and as we will see, they greatly affected Tek's direction and approach. There were rumors that Soros wanted to break Tek up and sell it off piecemeal. As we saw, an idea that had occurred to others. All parts of the company, including the Grass Valley Group, were under increased scrutiny.

Dan Castles, who we will look at shortly, was sent down to try to help Wilson right the ship. Castles eventually concluded that Wilson was not a good fit for the task at hand. Wilson returned to bay area employers. At one point he was President of Pinnacle Systems, another television equipment vendor, that for a while had a presence in Grass Valley.

With all he was facing in his position, he never set up a permanent household in the local area. Commuting between the bay area and the Grass Valley area, and staying on site three or four days a week. It was said that he spent a lot of his free time on a boat in the bay. He was forced out in the beginning of 1994.

Jerry Meyer - Tek President and Long Out

Lundeen ran Tektronix as interim president for six months, until October of 1990 when Jerome (Jerry) Meyer came in from Honeywell to take over Tektronix. He and Tom Long had an almost immediate falling out. One of the hats Long was wearing at the time was he was the head of Tek's development labs. A good part of the problem Meyer had with Long was that he was secretive about what they were working on in the lab so that if a Tek employee, not part of the lab left, they couldn't tell competitors what they were doing. Friedley liked Long, so he left him alone, but thought what Long was doing was unchecked, even though it was innovation. Meyer would not let it continue. He forced Long to retire, which he did and moved back to Chicago.It should be mentioned that one of Long's big accomplishments was to spin out the Tektronix Credit Union as an independent company. It still thrives today as First Technology Credit Union after absorbing the HP credit union and several others.

Meyer officially moved Kaplan over to the Communications Group and put him in charge.

Just prior to Meyer joining the company, Tektronix's market value was falling from about $1.3 billion in 1987 to less than $400 million in 1990, and as already stated the company was seen by many analysts as a potential take-over target. In September of 1990 the board of directors adopted an anti-takeover "poison pill," which entitled existing shareholders to purchase stock at half price if an investor acquired more than 20 percent of the company's stock. At the time, Jean Vollum, the widow of co-founder Howard Vollum, who had died in 1986, was the largest single shareholder with about 8.1 percent of the outstanding shares.

In 1991 things settled down for a bit. Tek had 12,000 employees on its payroll and had made a modest $45 million profit that year. Meyer was rewarded by being named chairman of the board as well as president.

That year NVISION, spun off two years earlier needed another cash infusion. Meyer had no interest in anything small. As we saw NVISION scrambled to find another investor, which they did. Meyer was known for having little patients, especially towards the Group. He was against anyone running the Group from having the President's title. He would say that Tek had one president, even though Grass Valley was a wholly owned but supposedly separate subsidiary.

Part of the problem was that the Group was 1/10 Tektronix's total revenue at the time, while it shipped half as much product as the rest of Tektronix. This ratio suggested that the Group was grossly underperforming revenue wise. At one point Meyer said it's time to fix the Grass Valley problem or bury it. What was happening to Grass Valley was that the market was rapidly changing. Competitors were introducing new digital products faster than the Group was. What happened to Grass Valley is the world shifted and they were slow to make the transition.

This was at the time when the 3000 composite digital production switcher launched with a number of problems.

Kaplan Out Castles Tek VP

GV was in dire straits in 1991 through 1993. At the end of 1992 Meyer unceremoniously dumped Larry Kaplan. Dan Castles was made head of the Communications Group and was sent down to oversee Wilson and help him fix the many issues.Kaplan was on the street for 2 to 3 years before he landed a gig at Sony. He was the Senior Vice President of Sony Broadcast for three years starting in February of 1995. After leaving Sony he started a company called Omneon. It pioneered the concept of video servers with distributed IO, drawing from central storage. It was the first real attempt at a video server that could be scaled to an enterprise wide size. The company was well funded by a number of venture companies, which was required, as it took almost five years before the company was able to ship anything. While the company tried to go public a number of times it stayed a private concern until it was acquired by Harmonic for $274 million in 2010. The company's co-founder, Donald M. Craig, was also a Tek alumni.

After a stint as an executive at Harmonic until 2012, Kaplan founded SDVI in 2013. SDVI is a media management and SAAS system (more on that in chapter 18). But basically it manages program content and deployment to end users. The elevator pitch is "The new company, called "SDVI" will take advantage of advances in IT technology and cloud-based services within the broadcast infrastructure to improve workflow and operational efficiencies."

"In the near future (and to a much greater extent than possible today) media facility functionality will be defined in software, mirroring the broader trends in the IT industry towards software defined data centers," Kaplan wrote in his blog. "SDVI will combine these technological shifts with intimate knowledge of media workflows, to provide revolutionary solutions to content owners, distributors and media facilities."

Kaplan's SDVI appears to match advice he once gave to Jim Michener. "You should start a virtual company. A virtual company is one where you have very few employees if any. Pick a specialized niche, and a specialized customer set. Some thought that Sony was a big paycheck where he could gather cash to start his virtual company, Omneon. But Omneon turned out to be too big of a niche to be something small enough where Larry would be able to keep all the balls in the air at one time. Larry appears that he might have reached his goal with SDVI."

So Michener took Larry's advice after he left the Group and for 20 years was a one man virtual company. Bob Cobler also took Kaplan's advice and started a virtual company in retirement. He started High Sierra Antennas as well as making high end DVD players, DVD players that put out SDI.

Lucie Fjeldstad - Tek VP

(Anyone have a better/larger photo?)

(Anyone have a better/larger photo?)

Lucie J. Fjeldstad, joined IBM in 1968 as an associate systems analyst in the Federal Systems Division. At IBM she held positions in planning, programming, development, marketing, finance, and executive management. In 1983, she was named laboratory director at the Endicott engineering and programming facility. She kept moving up. In 1986, Fjeldstad was named an assistant group executive; in 1988, she was named assistant general manager of finance and planning for the IBM Personal Systems line of business. She was even elected by the IBM Board of Directors as a corporate officer in June 1988 and was named president of the Multimedia and Education Division in June 1990. In this position, Fjeldstad was responsible for IBM's worldwide strategy and direction in the multimedia market and in high performance computing.

In the early 90s Fjeldstad showed up in Hollywood to preach the digital gospel in the name of IBM. She was in her late 40s at the time. She claimed that when digital technology hit publishing, filmmaking and music, "you won't be able to think of these as separate industries." Until her retirement from IBM she pushed digital production, multimedia, fiber optic distribution networks and high-level mergers at conferences and over lunch with studio execs.

At IBM, as a V.P. Fjeldstad led a team of hip, young, bright execs who thought they would change how Hollywood worked. Through Fjeldstad, IBM was going to put its corporate might at the service of Hollywood. Being Big Blue's point person in the re-making of the industry, Fjeldstad had her share of excitement. "Everybody is dancing with everybody," she told Variety in 92. At that time it was widely rumored that IBM was trying to cement a union with Time Warner.

But then the music stopped. IBM lost $5 billion in the last quarter of 1992, setting a record at the time. It was considered an unshakable employer and Wall Street performer. At the time it was clear that its fortunes would not turn around soon. It was struggling at the time to contract its work force. It had to develop new products and fend off competitors that it had not taken seriously. Its problems were being compounded by a worldwide recession at the time. Sales of its hardware had declined 20 percent in the last quarter of 92. Most of IBM's fourth-quarter loss was due to special multi-billion-dollar deductions taken to finance early retirements, production-line shutdowns and other steps in its restructuring program. It was the first time that revenue failed to cover even its operating expenses. IBM had lost almost $3 billion the year before. Beset by these financial problems, IBM never completed the Time Warner deal. Frustrated not only by IBM's slow-moving bureaucracy, but that a lot of what she envisioned was then on hold, she retired from IBM on May 31, 1993. At one time she was the highest female at IBM and was responsible for IBM investing in the digital media domain.

She spent some time in equestrian pursuits at her father's horse ranch in Northern California. She once said "I grew up on a horse." She also spent time at home with her husband in Connecticut. She started consulting for start-up interactive companies, as President and CEO of Fjeldstad International. Meyers brought in her consulting group to look at the video business in 1995, the person who did the summary presentation was Fjeldstad. She claimed that TEK/GV wasn't doing the business justice. So after a little deliberation Meyer told Fjeldstad that if you see this potential we don't, why don't you come in and run it. People in GV/Tek soon heard from IBM folks about how much she was despised, and they said you don't know what just happened. She was a breed that even with the likes of Yocam, and Meyer, Tektronix, or the Group had never seen before. Some think that she might have been hired to fend off Soros, that she was a trophy hire.

Soros thought at times the company had too much cash on hand, and that the separate parts of the company were underperforming. By August of 92 the Soros group had 12.6% of Tek stock. He had become a force that had to be reckoned with. Meyers wasn't keen on breaking up the company so quickly. The biggest perennial thorn in the side of earnings had become Grass Valley. Meyers was looking for a fresh approach. Maybe an outsider without any of the pre-conceived habits, customs, or momentum could set the Group in the right direction.

She joined Tek as a Vice President and President of the Video and Networking Division. (When? Was Dan Castles moved to GVG VP/GM?) When she joined the company it had annual sales of $1.4 billion. She and her husband moved to the Northwest. Fjeldstad immediately made plans to once again be around Hollywood "a lot more than in the past two years," she was quoted at the time. Her plan was still to marry high tech with entertainment. Ironically, at about the same time IBM hired a new Hollywood evangelist, a former AT&T multimedia exec Rick Selvage, to continue what Fjeldstad had done.

![]()

In 96 Tek announced large systems contracts with U.K's Central Broadcasting to be built around the Profile line. The Profile had been introduced a year earlier, and it was a bright spot in the whole Video Network Division's (VND) product lineup. VND was the latest name applied to what was the Communications Division. Announcements and articles at the time made no mention of the Group's involvement. While Profile DDRs were to be central to the project's digital television integration plans. There was very little mention of what the Group had to offer. In an effort to show that Tek was a leader in digital television, Senior Engineers David Fibush, along with Bob Elkind in the early 90s produced a series of of white papers on implementing, maintaining, and testing digital video and audio. Many of these papers were treated a primary sources when it came to video and audio digital signals. The Group genuflected to the Tek mother ship when it came dispensing digital insight.

It was at this time that, lead by Fjeldstad, that thought about the Grass Valley brand becoming non-relevant. Fjeldstad was much more familiar with how Hollywood worked, than how television, especially live television, worked. While today the same basic media/video/audio technology is in use by both cinema and television folks, then video technology was not yet ready to replace 35mm film cameras. Plus the electronics for video cameras to produce the film look, was in it's infancy.

Also at that time the belief that all you needed are computers, and not specialized boxes like the Group made, was taking hold. While that is what is finally happening today as we will see, it was a concept ahead of it's time in the mid-90s. Computers ran on Pentium processors, and Win95 or NT. Even Tek's marquee digital video product, the Profile, while controlled by microprocessors, the video and audio was still all processed by dedicated video, and audio, albeit digital, circuits.

A few of the Groups products now were dual branded with GV and Tek logos. "We've turned ourselves upside down in the past 18 months," she said at the time. "We've gone from being a box company to an integrated solutions provider," in a veiled dig at what the Group had been doing. She stated four "cornerstones" for Tektronix's digital strategy.

They were the Profile video disk recorder with a "plug-and- play" architecture. This was to allow the Profile to be the center of a digital facility which would allow "every other vendor that wants to plug and play" to connect to it, as she put it. The second was FibreChannel Networking. This was a technology that was originally designed to replace the old parallel SCSI connectivity between the computer and external storage. It's original concept was to allow many servers to draw media out of a single, or even multiple, disk storage systems. Soon many in the industry thought that maybe it's reach and use could be expanded to be a competitor to Ethernet, which while ascending in dominance as a computer network technology, hadn't yet been crowned the network technology of choice. Some believed that FibreChannel would be how media would be transported in digital facilities.

Third and fourth, were the MPEG and 4:2:2 standards. As we have seen MPEG is a way not only to compress individual frames of video, but to spread that efficiency over multiple frames in a video stream. 4:2:2 if you remember is the sampling rate between the monochrome and color components of the video. Tek wasn't out on a limb here as that is what the industry had settled on, and they would just go along.

The Group's claim to frame was the video production switcher. That along with audio and video routing, and the modular "glue" products weren't even mentioned in the grand scheme of how Tek and she saw the digital future. In fairness in the first couple years about 1500 Profiles shipped. The product was a hit. Fjeldstad thought that the market for GVG was going to be in editing, not production and transmission. That mindset was, and is still, often found among computer and IT folks that migrate into the real time video and audio media realm, from one where a certain amount of latency is the norm. Many who see a video production switcher control panel for the first time marvel, and wonder why all the rows of buttons, when GUIs are now the rule. Again real time actions and reactions to switching live video require instantaneous response. Today many things about switcher setup are done with GUIs, but the panels reveal that much cannot be, at least not yet. That said, it was not only Lucie Fjeldstad that had that mindset.

To many it soon became apparent that Fjeldstad didn't have a clue about the professional video industry. She had some very strong ideas about how Tek's VND should be run, and it definitely did not revolve around the Group. To facilitate her vision, she needed to control the narrative concerning her moves. Fjeldstad had her own publicist, Karen Curso, who came in handy for the 96 NAB convention.

In the planning for NAB 1996 Curso planned a big shindig. Curso did not come cheap, as she was on a $25-$30,000 monthly retainer. For the show she had a jazz group, Tom Scott and the LA Express perform. The soirée was at Mandalay Bay. There Fjeldstad proudly announced that she had acquired Lightworks Editing Limited for $27 million. The company was founded in 1989 by Paul Bamborough, Nick Pollock, and Neil Harris. The company over its lifetime had brought in only a few million in revenue as they had a niche customer base. The company's Editor was geared for film, and not television. Fjeldstad wanted to be a player in the Hollywood scene. Never mind the Group was already entrenched in Hollywood. Some in the industry called Lightwork's editor "Might works."

Films done with the editor amounted to Pulp Fiction 1994, The Cure 1995, Congo 1995, and Romeo + Juliet 1997. Interestingly there were no more done with the editor until 2001, after Tek sold it off in 1999.

Fjeldstad had done this on her own, so it had to succeed. She wanted to make good on the claim that she put GV in the editing business. Not mentioned is the fact that GV had been in the editing business since Dan Wright had acquired ISC in 1985. Still the transition from editing system that required dedicated rooms to a true desktop had not been easy on the group. The company had made three aborted attempts at such an editor before the Video Desktop 2 non-linear editor was finally nearing its launched.

Besides the havoc brought upon the editor efforts of the Group, she tried to eradicate the entire MPG (modular) division, by eliminating funding for any new research and development for it. The Group had cut its teeth in broadcasting by selling modular products. Not a reason to keep it she insisted. The reason this was a mistake, besides the fact that it made the company money, it was one more entry path into a facility, as these products were considered the "glue" that interconnected the "shiny" parts of a facility, the studios, and control rooms. Often when a customer bought a new switcher, they were rebuilding parts of the facility around where the new switcher would go, and that usually required modular products. They made for easy add-on sales for the "shiny" stuff.

The reason she eliminated it was she deemed modular projects as not strategic. Strategically, the goal is to turn a profit. To do that your business needs to competently solve problems for your clients. This is a business where the essential players strive to offer complete solutions. As we have seen, and as we will definitely see later in this book, the goal for many is to bulk up in the breadth of solutions offered. Yes, there is always room for niche players offering a "box" that does a particular thing. But the Grass Valley mindset had traveled very far from that position.

Also in 96 it was announced that Tektronix, not the Group, was buying an asset purchase of NewStar from parent company Dynatech based in Madison, Wis. Newstar was a television newsroom asset creation and management system. NewStar newsroom computer systems at the time were installed at more than 300 sites worldwide, and it employed 40 people and had roughly $5 million in revenue. NewStar originally operated as a separate business unit within Tektronix's Video and Networking Division. NewStar had what was known as a integrated solution of the Tektronix Profile digital disk recorder and EditStar editing software. This combination allowed a journalist to compose scripts and perform cuts only video editing.

Fjeldstad called the NewStar buy "the critical missing link" to Tektronix's news solutions for broadcasters. While Newstar already was a reselling partner of Tektronix digital disk recorders, Fjeldstad said that Tektronix's "modus operandi" was to buy integral pieces of the systems it sells and merge them into its Video and Networking Division, a strategy it has employed with Grass Valley infrastructure products and Lightworks nonlinear editors.

The take away here is that previously the Group was the bulk of VND, now it was just another piece like the other recently acquired companies. But as reported at the time "it's clear that the EditStar/Profile combination will be the main thrust of Tektronix's newsroom strategy." Again it was clear to Fjeldstad that editing and play out was central to her vision of the Tek's involvement in video, and that the Group made increasingly irrelevant stuff that should be pushed towards retirement.

The first meeting Fjeldstad ever attended down at Grass Valley she had every security person the company had in the front row. She was sick in the bathroom beforehand. She knew she would have very few allies in the room. She made it through the meeting without incident.

Fjeldstad commissioned a brand study on Grass Valley, Tek's Profile product, Tek itself, and Lightworks. She was looking to consolidate under one name.

Sample questions in that survey:

If a company were a person described that person. GV was considered helpful and friendly. The consensus on Tek was don't know, haven't seen my salesman in years. Lightworks-don't know them. Administrative assistant who worked for Kuca found that the company that did the study was paid $750,000. That study drove a lot of GV Loyalist out.

The premier editor under Tek's tutelage was to be Lightworks, and that the EditStar editor be used to create a edit decision list to be imported to a Lightworks editor for final edit.

Here was the case of what today might be called "the prison of two ideas." This tactic it put forward as you're for "my" solution, or for some dystopian result. Historically it was known as an Appeal to Extremes, or erroneously attempting to make a reasonable argument into an absurd one, by taking the argument to the extremes. Turns out Fjeldstad and the others were right, everything will run off common platforms eventually. As mentioned we're getting close to that today. But it couldn't be pulled off 30 years ago. The bet she made was that it could. The Group's products were passé, the future were common platforms, which at the time limited it to editing and video servers. So the two idea argument as applied to this is either your with the future, or you want the company to die.

Turned out like the climate change argument today, while there is general consensus that we must move towards renewable energy sources, the "two ideas prison" is framed as "we do it now, or you want the planet to die." Renewables are not yet ready to carry the full load, and in the 90s computer technology alone could not make up a television facility. VND revenue dropped precipitately.

By the end of 1997 Tektronix's video and networking division had been a drag on per-share earnings for nearly three years. As mentioned that lead to a $50 million charge against earnings. The division's $17 million loss in fiscal 1997 reduced Tek earnings by 35 cents per share. Tek would have made close to $4.00 per share. But it also makes the division's weakness more glaring. The division lost $27 million in fiscal 1996, $17 million in fiscal 1997 and $9 million in fiscal 1998.

The consensus was most everything in the division needed improvement. It needed to improve routine business operations, emphasize product marketing, increase the flow of new products and respond more quickly to technological change, particularly in the video and television industry, before the division could return to profitability. While Fjeldstad was definitely responding to technological change, her bets were wrong. Without the investment in the more mundane, "old school" products that the Group traditionally delivered there was a dearth of new products. Many were getting long in the tooth. A few termed the direction under her watch as the "Lucietainia."

There was another very large factor that was holding back the "common platform" approach; High Definition. Standard definition used fairly high clock rates, 270 Mbits to be exact. HD used clock rates almost six times greater. At 1.5 Gbits this involved frequencies in the microwave realm. This would require multi-core microprocessors and graphics accelerators only available recently to handle real-time live HD. Now in the server and editor realm video compression is used to bring down the bit rate. But the higher the compression rate, the lower the quality. In real-time live situations, that is uncompressed, what is referred to as baseband signals, that was not happening on a practical level back then. That was another reason why the Group was slow to HD. The HD requirements would not jive with the common platform mindset at the time.

Going into 97 the only bright spot was that the Group won a $20 million contract with CBS Sports to provide TV production equipment for the network's coverage of the Winter Olympics in Nagano, Japan. "They're healthier, but they're not healthy," Michael Silbergleid, editor of New York City-based Television Broadcast Magazine, said at the time. "Their larger customers are extremely happy with them. But they still have a lot of work to do with their smaller customers." High end customers were happy with the features and performance of Grass Valley products. But the lower end of the market needed lower cost alternatives, which competitors were providing.

Part of the problem was Grass Valley offered over 1,500 separate products. The consensus was that they needed to get down below 500. Also as was mentioned previously, a couple extraneous things were going on. The Dot com boom was ramping up, sucking up some of the capital of their customers, there was general concern brewing about the Y2K issue, and most importantly the war between digital formats, whether it would be SD, or one of the two flavors of HD, was still up in the air. Customers simply did not know which technological format to buy products for.

On top of that, as previous mentioned, broadcasters were aware that soon they would need to invest in new transmitters, antennas, and often tower upgrades, for digital TV transmission that was going to be mandated. A new transmitter can come in around a million dollars. New antennas also, no not like the one that used to sit on your roof. Often the transmit version can weigh 30,000 pounds or more because they need to handle the massive amounts of power that are pumped into them. Add to that, for an interim period broadcasters had to maintain the old analog, and the new digital channels. That meant two of those massive antennas. This often meant tower upgrades, or even new towers. That prospect meant some television broadcasters were looking at a million or easily much more in upcoming expenditures.

The accumulation of the above and in the summer of 1997 the floor dropped out from under Fjeldstad. Sales for that quarter dropped over 15%. Tektronix started restructuring the division in late August. Lucie Fjeldstad was out, and Timothy Thorsteinson was her replacement. The next month major changes hit the Group and VND.

Grass Valley, which employed 550 people, laid off one–fifth of its work force, one hundred full–time employees and about 20 temporary workers. Another 35 division employees were axed at the company's Oregon headquarters, and 50 more were laid off at various other sites around the world. Altogether, Tektronix laid off 200 in its video and networking division. The cuts left VND with around 1,280 employees, of which 450 were left in Grass Valley. The Group now employed in the area about a third as many as it did at it's height in the 80s.

Tek addressed the Group's excess inventory issue by pruning obsolete product offerings. It trimmed its product roster from 1,700 offerings to around 500.

Fjeldstad went on to be CEO and President of DataChannel, Inc., a software development company. She also served on a number of corporate boards, and was also a member of the Board of Regents of Santa Clara University.

Dan Castles leaves

Back to 96, when Fjeldstad was still in charge, Jay Kuca, who ran marketing communications, and another Alex (???), a marketing manager were commanded to go to a new ad agency she had selected, having dropped CKS Partners. It had a beautiful view of the Embarcadero in San Francisco. The new agency asked the two to go through the Group's product lineup. So they proceeded to explain the Group's products to them. When they got to editors, some twit at the agency said those will go away because of Lightworks.

On the elevator ride down Alex asked Jay if he knew anything about it. Jay said no. They realized that Castles, who had been running the Group after Wilson was gone probably didn't either. Which turned out to be true. After Fjeldstad had come on board Castles became the GM of the Group, and technically reported to Fjeldstad. While Fjeldstad concentrated on the " big picture," Castles faced the day to day challenges of the Group. He certainly didn't need the sudden scrambling of their editing product lineup. Castles confronted Fjeldstad who told him to cancel the company's editors. The editors that she put out of business were VPE, overseen by Bob Lefcovich, and the Sabre editor, which was an evolutionary descendant of the ISC editor, and Video Desktop 2, the Groups first non-linear editing system, six weeks before it was going to ship.

Dan said no, as he believed the new non-linear editor would have competed very well against another local startup, IMMIX. Remember that editor was created by the group that suddenly left the group a few years earlier. He took it to Meyer, who had a couple of people look into who was right. They sided with Castles. That led to a showdown in front of Meyer. During the meeting Fjeldstad threw down her Tek badge and said if you side with him she was out. Meyers reluctantly went with her.

Dan managed to work about 8 months for Fjeldstad before he resigned towards the end of 96. He did so in a public place, a Portland Airport restaurant. She cried and said you can't do this to me. He said yes he could. What he had worked towards in the early to mid-90s, which was gaining traction was tossed aside in the space of twelve months to head off in a new uncharted direction. Castles had not only gained the trust of the Group, but he and his family had become part of the Grass Valley area community. Meyer summoned Castles up to Beaverton and said that they liked what he did and wanted to keep him with Tektronix. They even offered to move him wherever in the world he wanted. He declined. When it became apparent he was just going to stay in the area, alarm bells went off in the company. Showed something about the Tek's mindset. You'd stay in the area for the work, but never for any other reason. Some of this was based on the Bob Wilson mentality.

They offered him a generous severance package, which had a non-compete clause, and he had to agree he would hire no GV employees for a few years. He turned the offer down twice. The amount of the severance went up each time. The third time his wife said take it, which he finally did. At the time he had no desire to do anything but be a father to his two young daughters. For the rest of 1996 and through 97 he was a dad.

Castles was not the only one who left because of Fjeldstad. Jay Kuca left also and headed for stints at local tech companies Graham Patton and Sierra Video.

Tim Thorsteinson - Tek VP

As Lucie Fjeldstad's replacement as president of VND in late-August of 97, he came to video and networking after a stint as head of Tek's Pacific operations. While in charge of the Pacific theater, Thorsteinson is credited with increasing orders 24 percent in fiscal 1997. Orders for video and networking products in the Pacific region grew 20 percent in the same year. Thorsteinson had a reputation as Meyer's fix-it man. He was in his mid-40, and had grown up in the Sacramento area, of which the Grass Valley area was an extreme outpost of the metropolis.

He was not a "video guy." But Tek upper management was confident of his ability to get the business profitable primarily by improving day-to-day operations. Tek and Thorsteinson tried to view the preceding layoffs as a positive thing, an incentive for the remaining employees to work harder. That outlook did not sit well with the rank and file.

The layoffs that had just occurred looked good on the bottom line, but often layoffs would backfire. Earlier layoffs in 1994, when the company was slow to convert its analog products to digital, resulted in spin off companies that made their own impact in video technology, and in some cases resulted in more competition for the company.

To help Thorsteinson he inherited Larry Neitling, who was brought in from Honeywell by Meyer. He served under Fjeldstad and then Thorsteinson as the Group's GM. Meyers hired Neitling who is a cowboy, to come in and kick ass. As GM his job was mainly to worry about the day-to-day operations. He was in his early 50s at the time.

Thorsteinson graduated from the University of Pacific in Stockton, Calif. in 1976 with a BA in psychology. He was an athletic guy, he was a Quarterback and wide receiver on the college football team. He married his wife, Kimberly, an electrical engineer, the year after he assumed the reins of VND.

His first job was working at National Semiconductor, where he used his psychology background to bring in new hires and form teams to create semiconductor fabrication facilities. He then moved into the position of director of productivity and quality improvement. It was during that period, 1980 to 1985, that he said he learned to place an emphasis on product development.

He once responded to the question of how a Psychology major became a technology leader: "It's through osmosis and being around smart people," he said. "I've learned a lot about technology, and it's a little like art. I have a house full of beautiful art, but I can't paint; I know good technologists and technology when I see them. And that's been to my advantage."

He is known for a bit of arrogance, once saying, "If you're not a leader, and that means No. 1 or 2, you don't have the scale to afford the investment to stay as a leader. If you don't move your development process very quickly, you can't take advantage of the most current component technology, and, as a result, your price points and feature sets will be non-competitive," he says. "That's seminal to my whole view of the business."

In 1992, Thorsteinson, who was then vice president, human resources, and total quality, for Tektronix, made his first trip to see Grass Valley's operations.

When Thorsteinson took over GV in 97, they offered at that point lots of digital standard definition products, but any HD offerings were still at least a year away. Meyer hired Thorsteinson to sell a road map. To convince customers that they should buy the company's SD products for now, and if in the future they decide they need to go HD, that the company would replace the equipment for free.

As mentioned earlier that did not sit well with the only official Grass Valley company spin-off, now competitor, NVISION. NVISION was then directly completing against Grass Valley in modular, routers and switchers. NVISION's pricing for HD matched Grass Valley's pricing on their SD gear. The Grass Valley name and reputation held enough value still that most customers said they would wait. The other compelling reason to not worry about not going HD, besides all the money broadcasters were pouring into new digital transmission facilities, was that the majority consensus at the time was that if HD ever became predominant, and many industry pundits thought that it would not, it would be many years down the road. At the time no one yet foresaw what Philips would do in cameras in a few years, which allowed ESPN to mandate their facilities providers to do their shows in HD.

At the time Grass Valley Group was spending quite a bit on research and development, but it really wasn't delivering anything to the marketplace, and only 10% of the revenue was coming from products that had been introduced in the previous two years. At the 1997 NAB, there was only one new product. Everything else was four or five years old. With the exception of Profile server advancement, which was not out of Grass Valley proper, there was no technology pioneering going on at GV at the time. Grass Valley was re-discovering that when a company does not introduce new products you incur margin pressure from newer competition. The only bright spot at the time was the Profile. Its margins were good as it was an early entrant into video disk storage. In the analog days GV had such a commanding position that people would wait. Up to a point. And that point had passed.

Thorsteinson pushed for a redoubling of efforts to get HD products out the door. He also knew enough about the inner workings of Tek to know that they were now seriously considering selling off Grass Valley. He realized that he needed to make it a salable asset.

The other thing Thorsteinson did was to start funding MPG development again. Mark Hilton was tasked with doing that. He was hired by Tek in 1995 and worked a couple years in Oregon. Having grown up in the San Francisco Bay area he hated the constant rain. He saw an opening at Grass Valley. When he came to Grass Valley he knew nothing about broadcasting but got the job anyway in 1997. He moved down with his family and was the modular product manager. He was charged with getting GVG back into modular. The company had just moved into Providence Mine.

Hilton thought he was hired because he had a couple years of doing product management the Tektronix way. Tek was trying to influence the way Grass Valley did things. They were still trying to bring GVG into a larger video network division within Tektronix. He spent three years at it as a product manager getting GVG back into that biz. He built a team of about 15 engineers from scratch.

In 1998 the first GV HD products launched. They were master control switchers and the HD version of the 7000 router, along with HD versions of several modular products. VND still lost $7 million that year.

At that time VND was a scattered business unit that consisted of Grass Valley, the Lightworks London-based video editing operation, the Profile disk storage business, and Tek's efforts in IT network computing. Thorsteinson said "We're not running around figuring out who needs to be laid off or what division needs to be downsized. So the energy can shift to positive." He also said, "We saw three or four points of gross margin improvement last quarter and I would expect to see that kind of improvement every quarter."

He claimed that the company was now down to about 20 base products, not counting options, and that they were all digital, and that they generated about 60 percent of the revenue. The company's gross margins were inching up towards 50%. He knew that for the company to afford to invest in new products it had to have margins north of 50%.

Another thing about the market the company served is that it was essentially a large, but niche market. Even a company the size of Grass Valley would be doing well to have a few thousand customers. The market at that time was largely fixed. Most companies in that position would most likely see only a few hundred of those buying the bulk of what they shipped. Lowering prices, and margins would only incrementally rise volume, usually not enough to make up for the loss in revenue. The way to win was to keep technological innovation on going. Something Grass Valley had lost, but finally working at getting that mindset back.

At the time the entire market that Grass Valley served was around $6 billion. Compare that to the worldwide PC market at the time, a hundred billion. Grass Valley was in a pretty specialized market. At the time it was thought that because the industry was in the beginning stages of going digital that the market would spike for a decade or so.

Even with the company's products, between Grass Valley itself, and all the test equipment that Tek offered, and there are scopes of various types throughout a television facility, Tek was at the time number two if you inventoried the average facility. Sony was the market leader because they sold tape decks and cameras. At the time Grass Valley did not. But as mentioned Tek's Profile disk recorder was a very bright spot for VND, as broadcasters were warming up to the idea that programming and commercial inventory could safely reside on disk, and not reside on video tape. So the $1 billion broadcast tape market was shrinking dramatically, and the soon-to-be $1 billion disk storage market was growing at 40 or 50 percent per year.

One thing Thorsteinson did foresee was the rise of software to predominance as a delineation factor in the market. Back in the analog days, the analog signal required a lot of tweaking and specialized hardware. Something that Grass Valley was very good at. Better than most of their competitors. They were able to get their products to do things nobody else could. But the move to digital leveled the playing field. It got a lot more like building PCs. So, the value had to be in the software application. The plan was to write specialized software applications around customer need. Back then he, like Fjeldstad and others before him, predicted that products were going to eventually use standard platforms, and that software was what would define the difference between competing products. Even at that time software engineers already outnumbered hardware engineers.

Also like Fjeldstad before him, he was wrong about the time frame. He predicted it would happen in three to five years. The processing horsepower of microprocessors at the time would need 15 to 20 years more development before that could happen. The other thing that he did not realize, even as a psych major, is that psychologically people will not pay tens, or hundreds of thousands of dollars for software based products, like they would for hardware, as we will see later.

While the industry was moving forward with digital, there were not many early adopters for HD. The market was only $100 million, spread over the next few years. After the ESPN HD initiative the market was at a billion dollars a year by the mid-2000s. As we have mentioned the industry was at an inflection point, with a fair amount of uncertainty. VND, along with the test gear aimed at television was about 25% of Tek's revenue. To stay up with the future growth of the rest of the company VND would need to also grow at that rate to be a net contributor. It was becoming apparent that was not in the cards.

With revenue not advancing at the desired rate, Tektronix got into the habit of telling VND at the end of the year they would reduce budgets - that meant reduce expenses or people. Often there were December layoffs though the last half of the 90s. Towards the turn of the century Tektronix was ready to take things apart.

Tim Thorsteinson is someone who will show up over the rest of the Grass Valley story, as he had three stints associated with Grass Valley. During his career he also ran Leitch, Harris Broadcast, and Snell & Wilcox. Over 20 years he was involved with the sales of five companies or exits as he likes to say.